An essential figure of 1970s European cinema, Romy Schneider always said there were three people who played a decisive role in her life and work as an actress: Alain Delon, Luchino Visconti and Gabrielle Chanel. She often expressed her gratitude towards Gabrielle Chanel for saving her from the character of the Sissi films, which had become suffocating, and had her fixed like a butterfly, an eternal child, by the gaze of others.

“Chanel taught me everything without ever giving me advice. Chanel is not a designer like the others… Because it’s a coherent, logical, ‘ordered’ whole: like the Doric order or the Corinthian order, there is a ‘Chanel order’, with its reasons, its rules, its rigours. It is an elegance that satisfies the mind even more than the eyes,” she confided.

A new silhouette, a new language, a new destiny. Sissi was no more, Romy Schneider was born, and it was Luchino Visconti who introduced her to Gabrielle Chanel so that she could dress her for his short film, Le travail, part of the collective film Boccace 70.

For the first time, Romy Schneider, who seduced, loved, governed, was passionate about reading, no longer had anything of the ingenue about her, and all this in an apartment that resembled that of Mademoiselle on the rue Cambon. The same bookcases, the same beige sofas, the same wing chairs. From then on, the actress wore CHANEL, both on screen – in Alain Cavalier’s Le combat dans l’île, released in 1962 – and off.

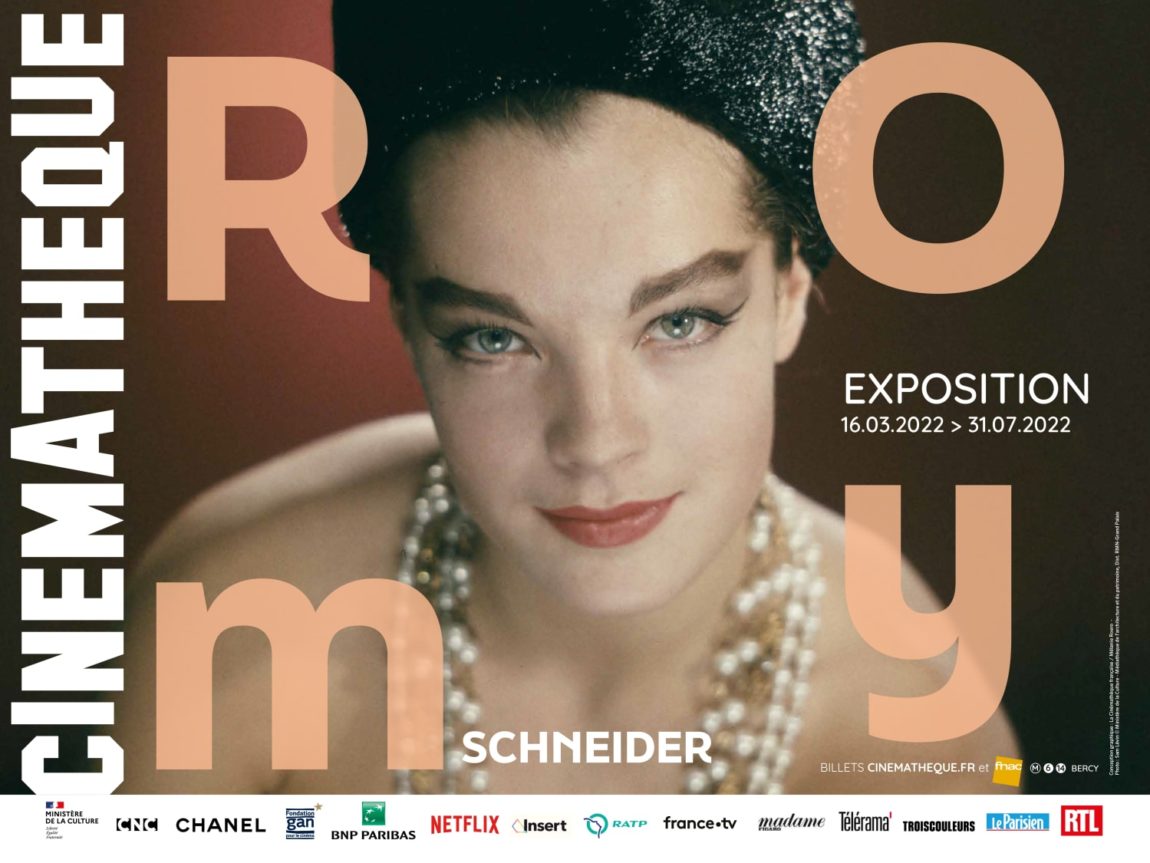

For the Romy Schneider exhibition, CHANEL is lending a mottled tweed suit from the Fall-Winter 1961/62 Haute Couture collection, similar to the one worn by Romy Schneider in the Visconti film, as well as five photographic prints taken between 1961 and 1965 by Shahrokh Hatami and George Michalke.

An eternal friend of the House, Romy Schneider will forever be an inspiring embodiment of the CHANEL allure.

Comments are off this post!