A new arrival in the artistic field of the 20th century, cinema intersected paths with Gabrielle Chanel’s extraordinary career in a continual creative dialogue, the imprint of which the so-called 7th Art still bears today. Barely ten years separate the birth of Gabrielle Chanel in 1883 from that of cinema in 1895, a prophetic coupling for these two revolutionaries who came into the world at the end of the 19th century (for the former and 1895 for the latter) to incite newness and to play a unique and innovative role.

She was still a child when cinema sparked an unprecedented revolution in the artistic landscape at the beginning of the 20th century: to set images in motion. Having become a designer, it was also this motion that she placed at the heart of her idea to free up the body and give rhythm to female silhouettes. The film of the CHANEL’s allure was starting.

Her intuition quickly enabled her to understand the importance this new artistic medium would have for 20th century culture. She recognized the need to bring fashion and cinema together: “It is through cinema that fashion can be imposed today ”(1), she said in 1931, well aware of its powers of dissemination and the visibility it provided to a larger audience.

That same year, the film magnate and producer at United Artists, Samuel Goldwyn, asked

Gabrielle Chanel to dress his actresses, a new project particularly well accomplished in Tonight or Never (1931), where Gloria Swanson wears a wardrobe created by Chanel. Refined to the extreme, a bottle of N°5 perfume even slips into the decor as if to reveal Gabrielle Chanel’s overall concept of a woman’s allure.

But the critics and actresses would find this lesson in Parisian elegance too simplistic for Hollywood. Refusing to compromise, Gabrielle Chanel slammed the door on Hollywood, and left with something she was absolutely certain of – a keen sense of photogenics which allowed her to master the art of choosing a cut and a fabric capable of flattering the silhouette and perfectly catching the light on screen. Costume and fashion now formed the architecture of a scene. Sensitive to the composition of a scene and an image, she then asked the future filmmaker, Robert Bresson, to photograph her fine jewelry collection Bijoux de Diamants (1932). Bresson’s unique sense of framing and light had certainly not escaped her.

Back in Paris, Gabrielle Chanel collaborated with French directors in various different ways:

Marcel Carné on Le Quai des Brumes (1938), Jean Renoir on La Marseillaise (1938), The Human Beast (1938) and The Rules of the Game (1939), for which she designed the costumes for all female roles.

The attitude of one of the actresses in this film posed with her hands in her pockets – embodied the feminine masculine style dear to Gabrielle Chanel. On the film’s release war was declared, and it would be Gabrielle Chanel’s last artistic collaboration with pre- war cinema.

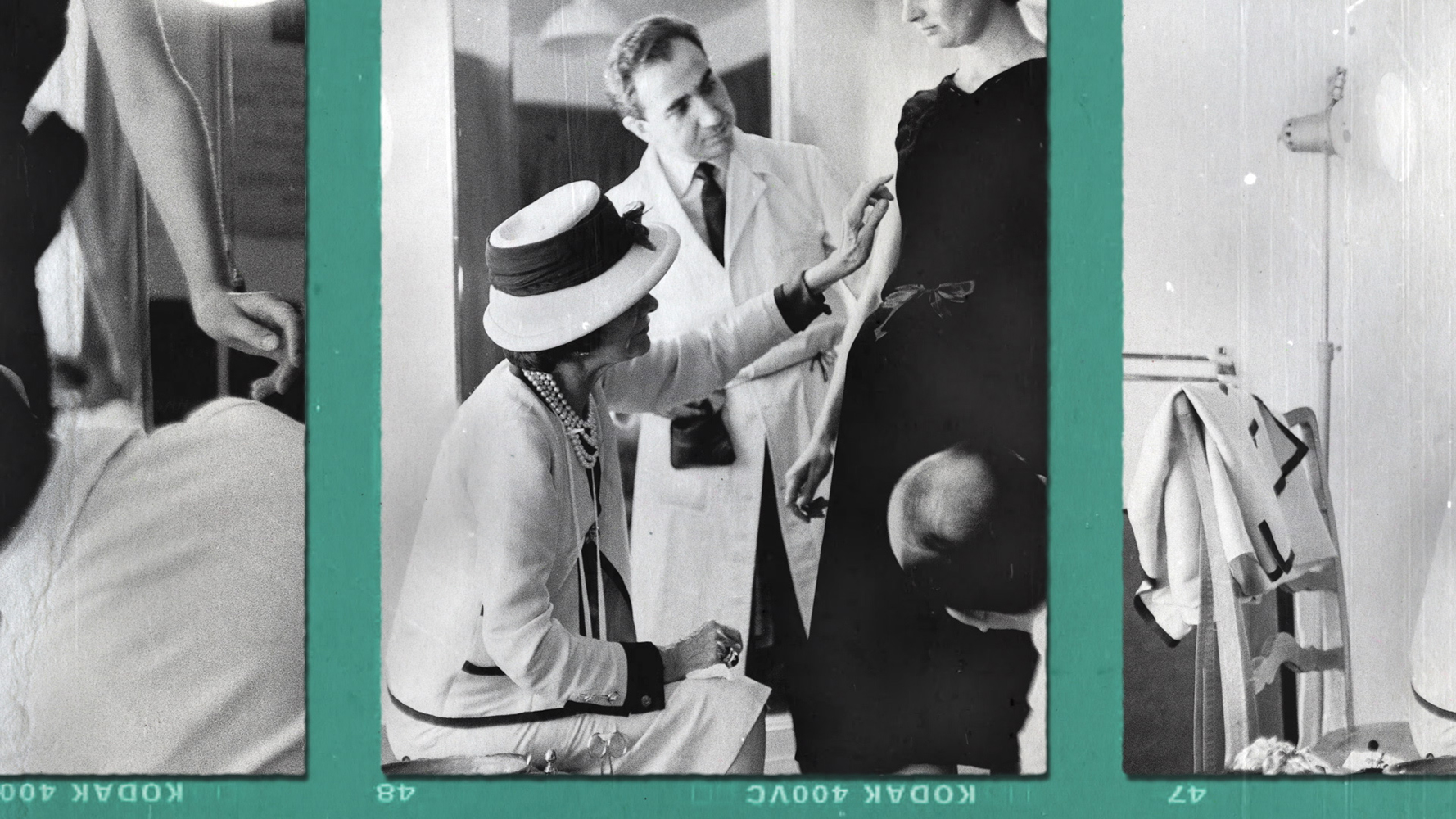

Upon her return to the fashion scene in the 1950s, Mademoiselle’s vision of fashion as being very much part of real life was embodied by the iconic tweed suit that perfectly matched the modernity of an emerging cinema aesthetic: The French New Wave.

Jeanne Moreau, who became a close friend of Gabrielle’s, naturally chose CHANEL outfits for her roles in The Lovers (1958), Elevator to the Gallows (1958) and Les Liaisons Dangereuses (1960), constantly moving back and forth between the screen and the street, blurring the distinction between the two. As perfect incarnations of modernity’s present, many of the New Wave actresses adopted CHANEL in their everyday lives, thereby testifying to the CHANEL allure – the ability to embody timeless modernity.

This search for elegance that is both rooted in time and timelessness is particularly evident in

Last Year in Marienbad (1961), where Alain Resnais asked Gabrielle Chanel for costume designs that evoked both the film stars’ personalities and the 1920s. Pieces from her Haute Couture collection clothe the actress Delphine Seyrig who underwent a total physical and gestural transformation for the film.

Between Gabrielle Chanel and this new generation of filmmakers and actresses, the artistic dialogue was fruitful, even very often, friendly. She found Anna Karina her name and Visconti handed her Romy Schneider: “Chanel taught me everything without ever giving me advice. Chanel is not a fashion designer like the others … It is an elegance that pleases the mind even more than the eyes.” (2) Romy Schneider burst on to the screen in Boccaccio ‘70 (1962) where the CHANEL universe appears in every scene. From the suit to the quilted bag, from the pearl jewelry, and two-tone shoes to the N°5 perfume, it is a true manifesto bursting with Romy Schneider’s talent as an actress and with the CHANEL allure.

At the heart of young cinema creations, and at over 70 years of age, the designer remained more than ever, “a part of what is going to happen” (3).

From Hollywood’s golden age to the French New Wave and on to avant-garde cinema, Gabrielle Chanel’s imprint has stamped modern cinema icons with the sign of modernity. CHANEL’s style remains forever imprinted in the credits of women’s lives, both on stage and in the street.

(1) La Revue du cinema, September 1, 1931

(2) Interview with Romy Schneider in Elle, September 20, 1963.

(3) Extract from L’Allure de Chanel by Paul Morand – Hermann – 1996, p204

Discover the new Inside CHANEL No. 28 episode on chanel.com.

Comments are off this post!