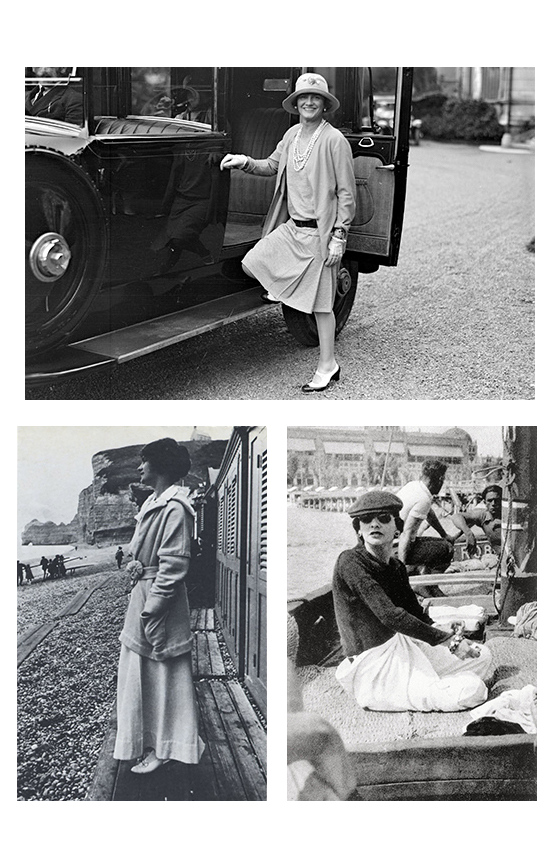

Like the stars that would form a constellation, certain cities made a lasting impression on Gabrielle Chanel. Deauville, Biarritz and Venice are part of CHANEL’s own astral chart. These destinations were linked to encounters, journeys, love or friendship stories, with some of the most important people in Gabrielle Chanel’s life. Each of these cities inspired the designer in its own way, helping to shape the CHANEL allure: horseracing, architecture and artistic movements down a sunny street, the presentiment of lifestyles to come, on the bridge of a boat or a beach, an instinct for future desires gleaned from simply walking and watching other women on holiday…

Gabrielle Chanel always observed the world around her, she nourished herself with it and drew from it like a living creative force.

In Deauville, at the turn of the century, she could already sense the primordial role awaiting her. History would prove her right: it was here she found success. It was here that the nascent century would witness the first triumph of a female entrepreneur. Biarritz, where she quickly opened another boutique, confirms that her vision of fashion, women and business was right. Then comes Venice, where Gabrielle discovers her fierce appetite for the arts and architecture. The city of canals shocks her with its beauty and provides the foundation of her cultural education.

In Normandy, on the Basque coast and in Venice, Gabrielle Chanel charted her way to success thanks to her incomparable instinct: always be in the right place at the right time.

Chapter 22: Deauville

Deauville witnessed the birth of the talent of an extraordinary woman. This new episode of Inside Chanel follows the footsteps of young Gabrielle.

The era is one of rediscovered happiness. The Franco-Prussian war is but a memory, and society is evolving. The 1900 Exposition Universelle highlights the latest technical feats while announcing the pursuit of the 19th century industrial revolution. With technical progress comes social and cultural advances. Suddenly the carefree and economic splendour of the new Europe could be enjoyed. The French Belle Epoque marks the advent of seaside resorts and outdoor sports. Deauville charms with its Anglo-Norman architecture, its beachside promenade and its wealthy population. Gabrielle Chanel makes her grand entrance in 1912 on the arm of Boy Capel, the English polo player who had become her lover and who she is madly in love with. Two years earlier, with his support, she had opened a hat shop in Paris and is now dreaming of establishing another. Deauville would become her showcase from 1913.

Quickly, with her sharp eye and eagerness for freedom, she realises that the constraints of sophisticated, corseted narrow dresses with their trains and complex headwear, must be revolutionized. It is here in Deauville that she imagines her first silhouettes in jersey. Here too, that she develops a taste for the elegance and practicality of menswear. Her inspirations? She draws them from Capel’s wardrobe, from the stable lads and the polo players at the racetracks, from the fishermen and even from the sea breezes that could blow fabrics away. By the water’s edge, this sun lover observes bathing ladies swathed in improbable swimming attire. Soon she would offer them fluid beach pyjamas and functional swimsuits, drop-front trousers and striped sailor tops, all comfortable and incredibly stylish. The beige of the sand would become one of her favourite colours.

Rebellious and unconventional, Gabrielle allows her skin to tan, she wants to cut her hair, has fun on the café terraces, in restaurants. She applauds the performances of dancer Loie Fuller and the Ballets Russes, for whom she would later design costumes and support passionately. With the help of her sister Antoinette and aunt Adrienne, her boutique on the rue Gautont-Biron is buoyant: full of women yearning for knitted sweaters, and outfits that are simple yet nonchalantly chic. Gabrielle Chanel had just invented sports fashion. The designer had anticipated the coming of a new era where women would adopt a new stance. A new story is being written, to which she too must take up a pen and contribute, wielding her scissors to inject a breath of fresh air.

Chapter 23: Biarritz

1915. As the world plunged into turmoil, Gabrielle Chanel continued to upheave conventions. Two years after opening a boutique in Deauville, the designer fell upon Biarritz and the Atlantic coast, a region favoured by the Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon. And it was here that Europe’s aristocracy, upper classes, and artists took refuge in those troubled times.

As in Deauville, she spent her time in the company of Boy Capel, then on shore leave. With the handsome officer at her arm, Gabrielle Chanel tasted the pleasures of the ocean, its perpetual motion, its strength and energy, so similar to her own. In a time when women were overcoming the absence of men and suffragettes were making their voices heard, Gabrielle Chanel followed her own tune and took a new and decisive step. The beaches, the sound of the waves crashing against the Rock of the Blessed Virgin, the wind in all its gentleness and violence, that particular red ochre they call basque, the villas with their architecture both simple and majestic: the designer intuitively felt that this might be a place for her. Specifically the 19th century Villa Larralde, strategically placed near the beach and the casino. And it was in this vast mansion that she decided to open her couture house. This was the next logical step after the success of her Paris and Deauville boutiques. Encouraged by Boy Capel, she hired sixty seamstresses. It was a bold move, but thanks to Gabrielle’s talent and reputation, the world’s élégantes flocked to her and the press sang her praises. The new boutique was an immediate success.

In Biarritz, Gabrielle Chanel achieved her most important victory: to prove that she was not only a talented designer but also an accomplished businesswoman capable of creating a true fashion and luxury couture house, as well as attaining financial independence. By 1918, in Paris, Deauville, and Biarritz, CHANEL employed three hundred workers, all women. As the war concluded, the world found itself once more in complete mutation: on the Basque coast, Gabrielle frequented Russian and Spanish aristocrats, and discovered other cultures, drawing from them the inspiration that would shape the CHANEL style. In Biarritz, Gabrielle Chanel proved that she owed her success to no one but herself, and found her true nature: fashion designer and businesswoman. She was more determined than ever to liberate women, to allow them to dance and swim, to soak in the sun, to love, to dare, to be themselves, unconstrained by clothing or the opinions of others. The discovery and installation of her couture house in Biarritz was a turning point: nothing would stop Gabrielle Chanel on the path to success. Step by step, with the successful launch in 1921 of her perfume N°5, followed in 1926 by her little black dress, she established her couture house as an icon of luxury. Her reputation spread far and wide, her designs highly sought by Americans and Europeans alike. Gabrielle Chanel had become what she had chosen to be: a free and independent woman.

Chapter 24: Veni

In 1920, Gabrielle Chanel was struggling to recover from the death, the previous year, of Boy Capel. To distract her from her woes, her closest friends Misia and José-Maria Sert decided to take her to Venice. Discovering La Serenissima was for the designer a renaissance. And the city, this cosmopolitan treasure trove of artistry, became one of her major sources of inspiration.

José-Maria Sert opened the city to Gabrielle Chanel, initiating her into its mysteries, its masterpieces, and its wealth of art history. The baroque and byzantine styles, the architecture of churches and palaces, the colours used by painters, the gracefulness of the Murano glass, all these splendours left a profound impression on the designer. From the famous painter Tintoretto, she borrowed the pigments for her first lipstick and, later, the famous lining of her bags. The mosaics, the gem-studded crosses, and byzantine medals of Saint Mark’s Basilica inspired her to create jewels she would wear on every occasion. The gold from the tapestries and religious icons found itself stamped onto her accessories, or translated to the leather of her shoes. The mirrors, the crystals, the Lion of Saint Mark, the multi-coloured woods, openwork or gilded, all of them found their way into her apartment on rue Cambon, an extension of her journeys and of this city that had become one of her favourites. For her collections, for her home, or simply for herself, she called upon Goossens, the famed jeweller, to design a line of jewels of byzantine and baroque inspirations, and to create crystal balls that she set upon a base of golden metal, in the exuberant Venetian spirit, one both precious and profound, rich in meaning and history.

The light and calm of La Serenissima finally appeased Gabrielle. Misia dragged her out into the aristocratic and artistic circles of Venice, and social life gave her back her smile and joie de vivre. Together, throughout the day, they met on the Lido. Gabrielle, in love with the sun, built a tan in her beach pyjamas, taking the time to invent a cork-soled sandal with simple straps, ordering them from a Venetian bootmaker. Her nonchalant elegance immediately seduced Venice’s high society and the holidaying jet set.

In the evening, they attended shows and sumptuous parties, and met writer Paul Morand. He would later describe them in his book, L’Allure de Chanel. Gabrielle also met Diaghilev, the dancer. It was a friendship at first sight. Later, she would secretly finance his ballet, The Rite of Spring. It was also her who, at his death in 1929, cut short a trip on the duke of Windsor’s cruise ship and arranged for the dancer to be buried on the isle of San Michele, a favourite of his. Gabrielle Chanel then accompanied the body on a gondola to its final resting place. Venice would remain one of her favourite ports of call, the one she would return to for short visits, but always with that same fervour and passion for the city that inspired so much of her life and fashion.

And then, of course, there was the lion. The symbol of Venice, the representation of Saint Mark, protector of the city. The winged animal echoed in Gabrielle like a sign, the same astrological one under which she was born. The sign that her strength was returning after the loss of her great love, Boy. The sign of an accomplishment after years spent building the foundations of her Maison in Paris, Deauville, and Biarritz. But also the accomplishment of a woman who said she chose who she wanted to be.

No Comment